Shree Kanjibhai Lalabhai Patel – Philanthropist par Excellence

“We exist temporarily through what we take, but we live forever through what we give.” Douglas M. Lawson

Within the confines of Mandhata Samaj and his local Dudley Community Shree Kanjibhai Lalabhai Patel will live forever as a man who gave so much for so long to alleviate need of his Community and hasten their progress.

On 14th July 2011, Shree Kanjibhai Lalabhai Patel breathed his last. We salute him and wish his soul everlasting peace.

Shree Kanjibhai hails from a little village called Nani Pethan in Navsari District in Southern Gujarat. He was born on 25th November 1925 to Kesiben and Lalabhai Jogibhai Patel, a simple village farming couple. He was the eldest in the family with three young sisters, Bhaniben, Paniben and Namiben. Before the eldest was nine tragedy struck. Their father passed away and the widowed mother was left to bring up the children the best she could. She indeed, do her best. She toiled in the field and in the home. She gave the children the love of their mother and father and made sure that Kanji studied up to standard seven.

Whether it was the impact of his father death or by nature Kanji turned out to be an introvert. He spoke less, observed, analyzed and learnt more than the boys of his age. Over the years one could observe that his perception went further and deeper than most of us.

No sooner he finished his primary education he got himself a job with Mafatlal Mills in Navsari. This was six miles away from his home. The roads in those days were nonexistent yet he walked to and fro, rain or shine to report on duty at seven each morning. The wages he earned were not enough to meet their simple needs so he found himself learning to sew and soon started augmenting the family income by working at home after mill work.

In 1945 he married Shantaben of Mokhla Falia in Matwad. This increased family responsibility put more pressure on young Kanji to try other radical ways of cashing on his technical skills of welding, sewing etc. In 1949 with the help of some friends he prepared to go to Kenya, in East Africa. This bid did not work out and so he was back to the mill job in Navsari.

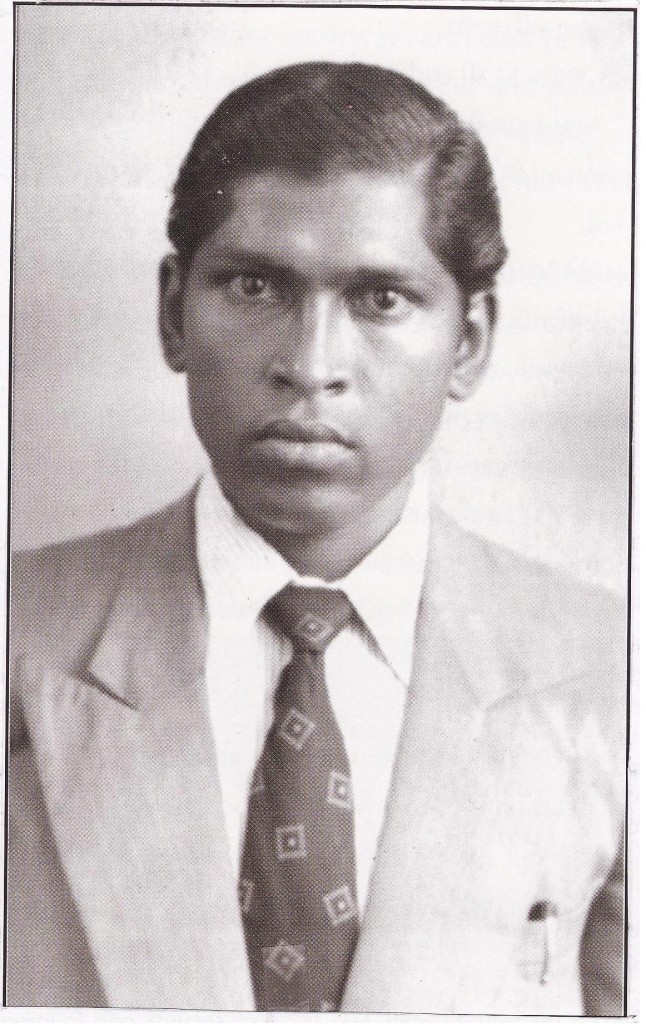

It was around this time and perhaps for the first time, possibly for a passport that young Kanji’s photograph was taken. Looking at this photo dressed in a double breasted suit and tie one could see the tall handsome man looking out far and wide. What attracts most is his deep penetrating, perceptive eyes that such a man cannot be held back for long. And so it proved.

In 1954 when few people from the area thought of going to England, he landed at Heathrow and made his way to Dudley in the Midlands. Here is got his first job in a local factory as a welder. With only working knowledge of the English language, still less the cultural mores of the New Land, he survived and survived handsomely by the dint of his mild manners, hard work and quick grasp of the surrounding needs, not only in the factory but also among the other workers who appreciated his talents and made him well liked.

Ever so observant, and sensing local needs of the increasing Asian Community in the area, and an opportunity to improve his financial position he learnt to drive, bought a battered van and started as a door to door salesman supplying clothing in his spare evening and weekend hours. Visiting people in their homes and getting to know and like them finally decided for him to lay down his roots in Dudley. He bought a large seven bedroom house and Shantaben and their four children joined him in 1959. Over the years another four children were born to the couple.

Arrival of Shantaben brought about a very welcome feminine touch. The house became a home in real sense of the word. Very shortly the family home became a hub for the community. Kanjibhai as we have seen was a source of information, help and comfort for a great number of our people who came to Dudley. Many of them were invited to stay with them until they found a job and alternative accommodation. Shantaben while looking after the growing family took great pleasure in serving the daily coming and going of the stranded guests. Her untiring support was a great support to Kanjibhai.

Demands of a growing family were forever increasing. He soon realized that a factory job or any amount of work in his spare hours was not the answer. The door-to-door job had already given him the confidence that he could run a business. And so it was. In 1964 he invested in a corner grocery shop. Hard work, sincerity and friendly attitude and complete honesty attracted more and more customers to his shop. Soon the corner shop was developed into a general store.

This brought him into close contact with other businessmen and the knowledge and confidence to think big. By 1978/79 his two eldest sons Dahyubhai and Kanubhai were also showing keen interest in business. So with their support he bid for a wholesale cosmetics business. In 1980 taking Dahyubhai with him they went to America to meet manufacturers and suppliers of cosmetic product. His reputation for honesty and clear business strategy they secured exclusive distribution rights for several line of cosmetic products. This proved to be a very profitable lucky break.

Back home the three directors organized warehousing, employed several competent people to help them with developing the growing business – signing up retail outlets and working out distribution logistics. The brothers were fast developing as keen a business sense as their father and within a couple of years the business was on a sound footing, becoming a financial success. Hard work and straight dealings with suppliers and customers were paying off handsomely.

Hardwork and honesty became the hallmark of this trio and the employees too realized bright future for them in this venture. They all pushed in the same direction. Business was becoming successful and the sons were taking on more and more responsibilities.

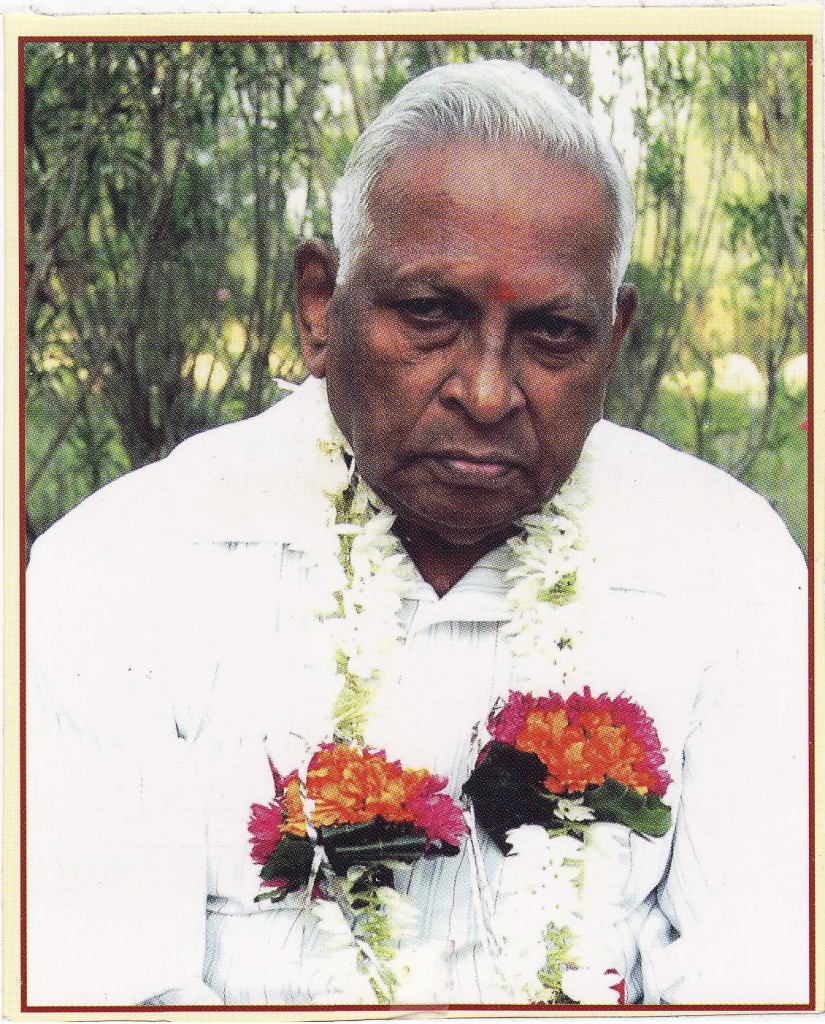

It was now time for Kanjikaka to relax a bit and turn his mind more to where his heart was – helping and supporting others. By our community standards he was considered comfortably rich. All his eight sons and daughters were at various stages of happily married or preparing for careers. And wife Shantaben was always by his side to wholeheartedly support him and take on the domestic responsibilities. Here was a unique family large as it was, where everyone respected everyone else and the elders particularly so. With hindsight it is not difficult to imagine. Kanjibhai and Shantaben led a very simple life, no vices and only goodwill towards all.

While still taking keen interest in the progress of the business Kanjibhai devoted more time thinking about the welfare of the community. As always there was not shortage of projects to support. Until now no one had gone empty handed. Now it was becoming a well considered regular flow. Over the years the list of his and the other members of the family’s donations grew longer and longer.

Let me quote just a few highlights:

Initial £45,000 to Shree Krishna Mandir, Dudley and more as and when needed. £15,000 to Shree Krishna Mandir, West Bromwich. £5,000 to Coventry and £3,000 to Walsall for similar purpose. He has been an active member and committee member of Mandhata Samaj UK since its inception and donated £1,100 to start off ‘Mandhata Pragati’ magazine and continued their support by way of placing full page colour advert year after year. He was also an active member of ‘Gujarati Association’ since 1965. In the cause of community welfare no one has gone empty handed from him.

His philanthropy did not stop to UK only. Since 1980 he has been a regular visitor to India and his native Pethan. Here in UK, for over thirty years he served as President of Pethan Mandal. In 1979 he initiated and financed the building of the waterworks in Pethan in India and in 1982 performed the opening ceremony which saw water piped to each house in Pethan. Gave hundreds of thousand Rupees to the local school and helped students with school kits etc. Started 11th and 12 standard studies, computer and English classes in Pethan High school and continued the financing the cost of extra teachers and equipment. When brought to his notice two bright boys – a muslim and a mistry- he financed the full cost of their higher studies. He also financed the setting up of Ambulance Service at Paschim Vibhag Keravani Trust.

Shree Mahesh Kothari led Mamta Mandir was an exemplary receiver of a donation of Rs. 11,11,111. This donation was to set up a printing press to train and make the disabled children of the Mamta Mandir to become self-supporting in later years. The opening ceremony of the press was performed by Shree Morari Bapu who named it Shree Kanji Lala and Shantaben Kanji Printing Press and honoured them both, praising lavishly. Mamta Mandir was a recipient of a lot more in later years.

Another notable donation was to ‘Dandi Nimak Satyagraha Trust’ of Rs. 11,11,111 to keep the ‘Gandhi Jyot’ burning in Dandi.

The above two donations, although not the largest shows his heartfelt awareness of the disadvantaged and his acute national feeling.

On 26th Feb 1997 my own Trust, Kantha Vibhag Friendship Trust organized a huge program in Kothamdi Gam to acknowledge and honour his contribution to the Koli Mandhata Samaj both in UK and India. Over three thousand people attended from far and wide to pay their tribute.

The story of his generosity which was an act of spirituality for him, does not end here. Several big and small organizations have benefited from his ever extending hand and now his sons and daughters have taken on the mental of their father.

Shree Kanjibhai Lalabhai Patel breathed his last on 14th July 2011 in the presence of his family. Large number of people attended his funeral and prayers were said at various meetings for the peace of his soul.

OM, Shanti, Shanti, Shanti.

(Note prepared by Keshavlal J Patel)

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Nana Sita – Gandhian and Civil Rights Leader and Freedom Fighter in South Africa

PDF File: Nana Sita – Gandhian – Civil Rights and Freedom in South Africa

PDF File: Nana Sita – Gandhian – Civil Rights and Freedom in South Africa

Name: Sita, Nana

Born: 1898, Matwad, Navsari, Gujarat, India

Died: 23 December 1969

In summary: Secretary of the Pretoria branch of the TIC, involved the Indian Passive Resistance Movement, member of the executives of the Transvaal Indian Congress and the Transvaal Passive Resistance Council, President of the Transvaal Indian Congress, in 1952, he led a batch of resisters which included Walter Sisulu, Secretary-General of the African National Congress during the Defiance Campaign, detained during the 1960 State of Emergency, banned person, imprisoned for defying the Group Areas Act

.Please note: this is an extract from E.S. Reddy collection of articles. http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/nana-sita

Nana Sita was born in Matwadi, a village in Gujarat, India, in 1898, in a family which was active in the Indian freedom movement. He went to South Africa in 1913 and lived for some time with J.P. Vyas in Pretoria, to study book-keeping. Soon after his arrival, Gandhiji, then leading a Satyagraha, went to Pretoria for

negotiations with General Smuts and stayed almost two months in the same house.

Identifying himself with the indentured Indian labourers, Gandhiji ate only once a day, wore only a shirt and loincloth, slept on the floor and walked barefoot several miles to the government offices to meet General Smuts. The contact with Gandhiji had a great influence on Nanabhai`s life. He followed the simplicity of

Gandhiji, and became a vegetarian, teetotaller and non-smoker. More important, he was always ready to resist injustice and gladly suffer the consequences.

He worked for some years in his uncle`s fruit and vegetable business and then started his own business as a retail grocer. He was active in the religious and social welfare work in the small Indian community in Pretoria. He joined the Transvaal Indian Congress and became secretary of its Pretoria branch.

During the Second World War, when the Government imposed new measures to segregate the Indians and restrict their right to ownership of land – culminating in the Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act of 1946 (the “Ghetto Act”) – militants in the Transvaal and Natal Indian Congresses, led by Dr. Yusuf M. Dadoo

and Dr. G.M. Naicker, advocated mass resistance. They were able to defeat the compromising leaderships of the Congresses and launch a passive resistance campaign in June 1946 with the blessings of Gandhiji. The campaign was directed by the Transvaal and Natal Passive Resistance Councils and over 2,000 people went to jail.

Nana Sita joined the militants as any compromise with evil was against his principles. He became a member of the executives of the Transvaal Indian Congress and the Transvaal Passive Resistance Council. He acted as Chairman when Dr. Dadoo was in prison or on missions abroad.

He led a large batch of “United Nations Day volunteers” – Indians, Africans and Coloured people – from the Transvaal in October 1946 and was sentenced to 30 days` hard labour. After release, he went to prison a second time. Almost every member of his family – he had seven children – went to jail in the campaign. His daughter

– Maniben Sita courted imprisonment twice.

Nanabhai – always wearing the Gandhi cap – became a familiar figure in the Indian movement. His courageous spirit was reflected in his presidential address to the Transvaal Indian Congress in 1948.

He said:

“Do we all of us realise the significance, the importance, the heavy responsibility that has been cast upon each and every one of us when we decided to challenge the might of the Union Government with that Grey Steel, General Smuts, at its head? Are we today acting in a manner which can bring credit not only to the quarter

million Indians in South Africa but to those four hundred million people now enjoying Dominion Status as the first fruits of their unequal struggle against the greatest Empire of our times?

“It is for each and every one of us in his or her own way to answer that question with a clear conscience. But let me say that I have nothing but praise for those brave men and women fellow resisters of mine. History has ordained that they should be in the forefront in the great struggle for freedom in this colour-ridden country of eleven million people…

“Over two thousand men and women have stood by the ideal of Gandhi and have suffered the rigours of South African prison life and they are continuing to make further sacrifices in the cause of our freedom. We at the head of the struggle cannot promise you a bed of roses. The path that lies ahead of us is a dark and difficult one but as far as I am personally concerned I am prepared to lay down my very life for the cause which I believe to be just.” (Passive Resister, Johannesburg, April 30, 1948).

The Indian passive resistance was suspended after the National Party regime came to power in June 1948, but only to be replaced by the united resistance of all the oppressed people.

In June 1952, the African National Congress and the South African Indian Congress jointly launched the “Campaign of Defiance against Unjust Laws” in which over 8,000 people of all racial origins were to court imprisonment.

Nanabhai was one of the first volunteers in that campaign. He led a batch of resisters which included Walter Sisulu, Secretary-General of the African National Congress. He came out of jail in shattered health.

The next year, when Dr. Dadoo was served with banning orders, Nanabhai was elected President of the Transvaal Indian Congress but he was also soon served with banning orders preventing him from active leadership of the community.

Yet, in 1960, during the State of Emergency after the Sharpeville massacre, he was detained for three months without any charges.

With the banning of the African National Congress and the escalation of repression, leaders of the ANC decided to undertake an armed struggle, taking care even then to avoid injury to innocent people. Those who believed in non-violence as a creed or could not join the military wing of the movement faced a serious challenge as even peaceful protests were met with ruthless repression. Nana Sita – with his Gandhian conviction that resistance to evil is a sacred duty and that there is no defeat for a true satyagrahi – was undeterred. Like Chief Albert Lutuli, the revered President-General of the ANC, he continued to defy apartheid – especially the “Group Areas Act”, described as a pillar of apartheid, which enforced racial segregation at enormous cost to the Indian and other oppressed people.

In 1962, Hercules, the section of Pretoria in which Nanabhai lived, was declared a “white area” under the “Group Areas Act”. He was ordered to vacate and move from his home – which he had occupied since 1923 – to Laudium, a segregated Indian location eleven miles away. He defied the order and was taken to court on December

10th, the United Nations Human Rights Day.

Denouncing the Group Areas Act as designed to enforce inferiority on the non-white people and cause economic ruination of the Indian community, he told the court overflowing with spectators:

“Sir, from what I have said, I have no hesitation in describing the Group Areas Act as racially discriminatory, cruel, degrading, and inhuman. Being a follower of Mahatma Gandhi`s philosophy of Satyagraha, I dare not bow my head to the provisions of the unjust Act. It is my duty to resist injustice and oppression. I have

therefore decided to defy the order and am prepared to bear the full brunt of the law.

“It is very significant that I appear before you on this the tenth day of December, to be condemned and sentenced for my stand on conscience. Today is Human Rights

Day – the day on which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was accepted by the world at the United Nations. It is a day on which the people of the world rededicate themselves to the principles of truth, justice and humanity. If my suffering in the cause of these noble principles could arouse the conscience of white

South Africa, then I shall not have strived in vain.

“Sir my age is 64. I am suffering with chronic ailments of gout and arthritis but I do not plead in mitigation. On the contrary I plead for a severe or the highest penalty that you are allowed under the Act to impose on me.”

He was sentenced to a fine of 100 Rand or three months in prison, and warned that if he failed to comply he would be given twice that sentence. He refused to pay the fine and spent three months in prison.

The next year, as he and his wife, Pemi, continued to occupy their home, he was again taken to court and sentenced to six months in prison.

The authorities charged him and his wife again in 1965. He appealed to the Supreme Court challenging the validity of the Group Areas Act. The matter dragged on for a year before his appeal was dismissed.

When the trial resumed in 1967, Nanabhai read a 19- page statement on the background of the Group Areas Act which he described as a “crime against humanity”, and said:

“The Act is cruel, callous, grotesque, abominable, unjust, vicious and humiliating.

“It brands us as an inferior people in perpetuity, condemns us as uncivilized barbarians… “One day the framers of this Act will stand before a much higher authority for the misery and the humiliation they are causing….

“If you find me guilty of the offence for which I am standing before you I shall willingly and joyfully suffer whatever sentence you may deem to pass on me as my suffering will be nothing compared to the suffering of my people under the Act. If my suffering in the cause of noble principles of truth, justice and humanity could arouse the conscience of white South Africa then I shall not have strived in vain… I ask for no leniency. I am ready for the sentence.”

Many Indians attended the trial and wept when he concluded his statement.

He was sentenced again to six months` imprisonment and served the term, declining the alternative of a fine of 200 rand. His wife was given a suspended sentence.

On his release from prison, he said:

“It is immaterial how many other people accept or submit to a law – or if all people accept it. If to my conscience it is unjust, I must oppose it.

“The mind is fixed that any injustice must be resisted. So it does not require a special decision each time one is faced with injustice – it is a continuation of one commitment.” (Jill Chisholm in Rand Daily Mail , April 6, 1968) .

Soon after, on April 8, 1968, Nanabhai and Pemi were forcibly ejected from home and government officials dumped their belongings on the sidewalk. But they returned to the home and Nanabhai never complied with the order until he died in December 1969.

Few others followed Nanabhai`s example of determined non-violent resistance in the 1960`s. The militants among the Indians, espousing armed struggle, had been captured, or went into exile, or tried to rebuild underground structures which had been smashed by the regime in 1963-64. The traders, who were severely affected by the Group Areas Act, had given up resistance after all their petitions, demonstrations and legal battles had failed. A silence of the graveyard seemed to have descended over the country.

But the resistance of Nanabhai was not in vain. It showed that non-violent defiance need not be abandoned even at a time of massive repression or armed confrontation. It inspired people in efforts to overcome frustration and apathy. The Indian Congresses, which had become dormant, were resuscitated in later years and helped build the powerful United Democratic Front.

Nana Sita`s children – Maniben Sita and Ramlal Bhoolia, both veterans of the 1946 passive resistance – played leading roles in the resurgent movement, defying further imprisonment.

As the freedom movement recovered, the Soweto massacre of African schoolchildren on June 16, 1976, failed to intimidate the people. Thousands of young people joined the freedom fighters. And many more began to demonstrate their support of the struggle and defy the regime, making several laws inoperative. The struggle entered a new stage.

The mass non-violent defiance campaign, which swelled in recent years like a torrent encompassing hundreds of thousands of people, has made a great contribution, together with the armed struggle and international solidarity action, in forcing the racist regime to seek a peaceful settlement. South Africa, the land where Gandhiji discovered satyagraha , has enriched his philosophy by adapting it under the most difficult conditions.

Nana Sita – who held up the torch when the movement was at an ebb – was in a sense the last of the Gandhians. The mass democratic movement now derives inspiration from many sources, including the experience of the long struggle of the African people and the Gandhian tradition cherished by the Indian community.

Nana Sita is remembered with respect as his colleagues in struggle – Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada and others now out of jail – lead the nation in its continuing efforts to eliminate apartheid and build a non-racial democratic society.

He passed away on 23 December 1969, shortly after the centenary of Gandhiji, at the age of 71.

Shree Kanjibhai Patel

Shree Kanjibhai Patel Shree Kanjibhai Patel

Shree Kanjibhai Patel