Gandhi in South Africa

Website: Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya

Website: M. K. Gandhi – Albert Luthuli Documentation Center

GANDHI IN SOUTH AFRICA (1893-1914)

While traveling by train to Pretoria, Gandhiji experienced his first taste of racial discrimination. Inspite of carrying first class ticket, he was indiscriminately thrown out of the train by the authorities on the instigation of a white man.

Gandhiji’s reaction was that of `David confronting the Goliath of racial discrimination.

Instead of fleeing from the seen, Gandhiji stayed back – for 21 years to fight for rights of the Indians in South Africa. By May 1894, he had organized the Natal Indian Congress. In 1896, he returned to India and enlisted support from some prominent Indian leaders. He then returned to South Africa with 800 free Indians. Their arrival was met with resistance and an inflamed mob attacked Gandhiji physically. Gandhiji exercised `self-restraint’. His philosophy of winning the detractors with the peaceful restraint had begun.

It yielded fruit. Under pressure from the British government the attempt to disfranchise Indians in South Africa was abandoned.

With the outbreak of the Boer war in 1899, Gandhiji enlisted 1100 Indians and organized the Indian Ambulance Corps for the British. Inspite of the Indian support, the Transvaal Asiatic Department continued its anti-Indian regulations. Gandhiji chose to support the British as he felt, “The authorities may not always be right but as long as the subjects owe allegiance to the state, it is their clear duty to…accord their support”.

Gandhiji was now the recognised leader of South Africa’s Indian community. By1901,he returned to India with his family. He travelled extensively in India and even opened a law office in Bombay. However, South African Indians refused to part with their crusader of justice.

He had to return to South Africa on the request of the Indian community in 1902.

By 1903, Gandhiji had begun to lead a life of considerable discipline and self-restraint. He changed his dietary habits, he was his own doctor, he embraced the Gita and he was confronting untouchability. By 1906, after undergoing many trials and tribulations of self-abnegation and eventually brahmacharya (celibacy), he had became invincible to face the South African government. Except God, Gandhiji feared nothing.

Influenced by John Ruskin’s preaching of rustic life, Gandhiji organized Phoenix Farm near Durban. Here he trained disciplined cadres on non-violent Satyagraha (peaceful self-restraint), involving peaceful violation of certain laws, mass courting of arrests, occasional hartal, (suspension of all economic activity for a particular time), spectacular marches and nurtured an indomitable spirit which would fight repression without fear.

In Sept 1906, he organized the first satyagraha campaign in protest against the proposed Asiatic ordinance directed against Indian immigrants in Transvaal. While in June 1907, he organized satyagraha against compulsory registration of Asiatics (The Black Act).

In 1908, Gandhiji had to stand trial for instigating the satyagraha. He was sentenced to two months in jail (the first time), however after a compromise with General Smuts he was released. Out of jail he was attacked for compromising with General Smuts. Unfortunately, Smuts broke the agreement and Gandhiji had to relaunch his satyagraha.

In 1909, he was sentenced to three months imprisonment in Volkshurst and Pretoria jails. After being released, he sailed for England to enlist support for the Indian community.

In 1913, he helped campaign against nullification of marriages not celebrated according to Christian rights. He also launched his third satyagraha campaign by leading 2000 Indian miners across the Transvaal border. By December, he was released unconditionally in hope of a compromise.

Gandhiji’s ahimsa (non-violence) had triumphed. Victory came to Gandhiji not when Smuts had no more strength to fight him but when he had no more heart to fight him. Much later General Smuts declared that men like Mahatma Gandhi redeem us from a sense of commonplace and futility and are an inspiration to us not to weary in well doing….’

_________________________________________________________________

An unconfident Mahatma Gandhi landed in Durban in 1893. Ten years later a much changed man stepped off a train at Park Station in Joburg, well on his way to developing a philosophy that would touch the world.

By the time he left South Africa for his native India in 1914, at the age of 46, Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha was fully realised.

Satyagraha is the philosophy of non-violent (or “passive”) resistance famously employed by Gandhi in forcing the end of the British Raj – but first wielded against racial injustice in South Africa.

This year marks the centenary of the beginning of the Satyagraha movement, based on a philosophy which originated in September 1906, born out of Gandhi’s experiences while living in Johannesburg with his family from 1903 to 1914.

Gandhi’s Johannesburg

Gandhi left his gentle footprint around Johannesburg: from the house in Albermarle Street in Troyeville, where he and his family stayed in the early 1900s, to Victory House in the CBD, where he was refused entry to the city’s first lift, to the Old Fort prison where he served two terms of several months each in 1908.

But perhaps the most significant site was the Empire Theatre – long demolished but originally on the corner of Commissioner and Ferreira streets – where the Satyagraha movement was born.

Birth of Satyagraha

On 11 September 1906, Gandhi chaired a meeting of more than 3 000 people there. The town’s Indians were protesting against the Transvaal Asiatic Law Amendment Ordinance, Eric Itzkin writes in Gandhi’s Johannesburg, birthplace of Satyagraha.

The ordinance required all Asians to obey three rules: those of eight years or older had to carry passes for which they had to give their fingerprints; they would be segregated as to where they could live and work; new Asian immigration into the Transvaal would be disallowed, even for those who had left the town when the South African War broke out in 1899 and were returning.

The meeting produced the Fourth Resolution, in which all Indians resolved to go to prison rather than submit to the ordinance.

Itzkin, Johannesburg’s deputy director of immovable heritage, quotes Gandhi as saying: “Up to the year 1906 I simply relied on appeal to reason. I was a very industrious reformer … But I found that reason failed to produce an impression when the critical moment arrived in South Africa.

“My people were excited – even a worm can and does turn – and there was talk of wreaking vengeance. I had then to choose between allying myself to violence or finding out some other method of meeting the crisis and stopping the rot, and it came to me that we should refuse to obey legislation that was degrading and let them put us in jail if they liked. Thus came into being the moral equivalent of war.”

‘Passive’ resistance

Despite Satyagraha, the ordinance became law in 1907, and non-violent resistance was used by the Transvaal’s Indians to oppose discrimination.

In 1913 it spread to Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal), where Indian coal miners downed tools.

The African National Congress (ANC), founded in 1912, was also influenced and used the philosophy up until the 1960s, when they switched to a policy of armed struggle to overthrow apartheid.

Satyagraha was also used by Martin Luther King in the US who, according to Itzkin, “accepted Satyagraha as the only morally sound method open to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom”.

__________________________________________________________________

Gandhi in Johannesburg

An in-depth story of the life of a religious man, a philosopher and an activist for free society, Mahatma Gandhi, is told in a mind-blowing exhibition at Museum Africa.

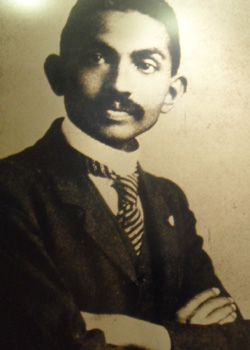

A young Mahatma GandhiThe exhibition, entitled Gandhi’s Johannesburg – Birthplace of Satyagraha, consists of pictures and snippets of history and tells of the years the world-renowned pacifist leader spent in Johannesburg, from 1903 to 1913. It reveals his founding of and growing adherence to his philosophy of satyagraha, as well as his devotion to equality for all and universal suffrage.

During Gandhi’s stay in South Africa, during which time it was a British colony, as was his homeland of India, the colonial government imposed discriminatory laws on various groups, including blacks, coloureds, Indians and Chinese. These groups were regarded as second class citizens and were not treated equally.

In demanding equal rights and an end to discrimination, Gandhi developed satyagraha, or soul force. He preached mass defiance and passive resistance to unjust laws, from the early 1900s. He advocated for the rights of people across the racial and religious spectrum, including blacks, coloureds, Asian, Indian, Chinese, Muslim, Hindu, Animist and Christian people.

So powerful was the philosophy that it inspired downtrodden people across South Africa, India and the world. The founders of the ANC adopted satyagraha in 1912, and the first mass anti-apartheid programme, the Defiance Campaign of 1952, followed the pattern of passive resistance set by Gandhi.

Civil rights

It was only in the 1960s, under increasing pressure from the National Party-ruled apartheid government and banning orders, that the ANC resorted to armed struggle. The exhibition reveals that satyagraha influenced other powerful political movements, such as the African-American civil rights groups, South Africa’s black liberation groups and India’s struggle for independence from Britain.

The Hindu Crematorium in Brixton, built in 1918, four years after Gandhi left South AfricaGandhi founded the British Indian Association in 1903, in pursuit of the resistance struggle, and was its chief strategist. In his resistance campaigns, he worked closely with the Hamidia Islamic Society, although he was a Hindu.

It was outside the Hamidia Mosque on 16 August 1908 that Indians and Chinese set alight more than 1 200 registration certificates in an outpouring of mass resistance to the colonial government’s decree that all people of Asian descent carry identity certificates.

The Hamidia Mosque, at 2 Jenning Street in Newtown, is still used today.

On the 23rd of the same month, another 525 registration certificates went up in flames. These demonstrations followed the passing of the Transvaal Asiatic Registration Act that year. It demanded that all people of Asian descent provide a thumb print in addition to their personal identification registration certificates.

If they failed to comply, they would be refused access to trade. In addition, those found without registration certificates could be deported or fined on the spot.

Location

The exhibition records that at the time, a great number of Indians, Chinese blacks and coloureds lived in a settlement on the western side of Joburg that was called the Coolie Location. The area is today known as Newtown.

The area was neglected by the municipality and became a slum. There were no proper roads, lighting or sanitation. As a result of these unhygienic conditions, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in 1904.

Gandhi, who was very much part of the community, nursed the victims in a temporary plague hospital set up at what is today 76 Carr Street. To quell the contagious diseases, the authorities moved residents to an emergency camp in Klipspruit, 21 kilometres south of Joburg.

Chinese passive resisters, with their leader Leung QuinnThe Coolie Location was burnt to the ground, and the Klipspruit settlement grew into Soweto. Newtown was later redeveloped into a business precinct for white-owned businesses.

Outspoken as he was, Gandhi blamed the city council for using the disease caused by municipal neglect as an excuse to destroy the Coolie Location. He was a lawyer and took on the government for expropriation of land in the area, a battle he never won.

Like many other activists who challenged the system, he was arrested, along with many of his followers. He appeared in court both as a prisoner and as a lawyer defending other satyagrahas. In all, he was imprisoned four times during his years in South Africa, two of those times in Johannesburg, where he was held at the OId Fort Prison

Prison

A range of pictures showing Gandhi and other inmates at the prison in Braamfontein – at one time the most notorious jail in the country – are on display. During the struggle of later years, many anti-apartheid activists were also incarcerated in the prison.

While Gandhi opposed the system of discrimination, he also made compromises. His first prison sentence, for example, ended in early release after he agreed to support voluntary registration in return for General Jan Smuts abolishing compulsory registration of Asians. Smuts, at the time the colonial secretary of the Transvaal, was his main political opponent at the time.

Visitors are also able to learn about some of the significant landmarks in Johannesburg that were touched by Gandhi. They include the Hindu Crematorium at the Brixton Cemetery. Built in 1918, it was the first Hindu crematorium on the African continent.

Through his interventions, the Hindu community obtained a suitable piece of land for the crematorium. Money for its construction – it was only built after Gandhi left South Africa – was donated by the community. The crematorium was declared a national monument in 1995.

Struggle stalwart Walter Sisulu unveils a tombstone for Nagappen, 20 April 1997In honouring his legacy, landmarks have been named after him, such as Gandhi Hall. The hall is located on the corner of Ferreira and Marshall streets in down town Johannesburg. It was built by the Transvaal Hindu Seva Samaj in 1939, and was used as a meeting place by the ANC and other anti-apartheid groups.

Satyagraha

Mentioned in the Gandhi exhibition are other followers of satyagraha, including those who died in the pursuit of freedom.

In one intriguing picture, taken on 20 April 1997, veteran anti-apartheid activist Walter Sisulu is seen unveiling a tombstone for Swami Nagappen Padayachee, an 18-year-old who died of pneumonia and resultant heart failure shortly after he was released from prison. Fellow prisoners reported that he had been physically abused by prison warders.

In spite of the injustices, discrimination and incarceration, Gandhi loved Johannesburg. In his farewell speech on the eve of his departure from South Africa he said Johannesburg was the place where he found his precious friends, and where the foundation was laid of the great struggle of passive resistance.

“Johannesburg therefore had the holiest of all holy associations”, he said.

Gandhi’s Johannesburg – Birthplace of Satyagraha is a permanent exhibition at Museum Africa in Newtown. The museum, at 121 Bree Street, is open from Tuesdays to Fridays, from 9am to 5pm. Entrance is free and there is parking in Mary Fitzgerald Square.

Read more: http://www.joburg.org.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7691&catid=88&Itemid=266#ixzz1s2WiP9M9

__________________________________________________________________

Gandhian Websites

|

A complete site about the |

|

|

|

|

|

A Place to learn about Gandhi, |

|

It is a superb site on |

|

An |

|

This site |

|

A beautiful site about |

|

|

|

|

|

A general site but includes |

|

Mark Shepard’s Gandhi Page: Mahatma Gandhi, |

|

Important |

|

A |

|

This site |

|

Gandhi |

|

A link to Mahatma Gandhi page from |

|

Information on Mahatma Gandhi and |

|

This is site of Gandhi |

|

Gandhi’s |

|

The site is on MK Gandhi Institute of non violence of Arun Gandhi, Mahatma |

|

Site by |

|

Quotations by Mahatma Gandhi |

|

On life and death |

|

History of Salt March 1930. Also |

|

Virtual Gandhi Ashram. |

|

|

|

Gandhi |

|

A brief yet informative |

|

|

|

Excellent website by Times |

|

A website by the government of India, has a superb section on |

|

|

|

On January 30th, 2008 it will |

|

|